The Truth About Pesticides in Thailand’s Food Chain

The north of Thailand is blanketed by rolling green hills and rice fields, while the south blooms in abundance with tropical fruits and vegetables.

Visitors to Thailand often laud the country for its healthy food — noodle dishes, curries, stir fried vegetables and tofu, and overfilling plates of rice.

These dishes are generally considered healthier as they’re freshly prepared and made with local produce, but if you’ve ever watched a street vendor make your food, you’ll have noticed the copious amounts of oil, salt, sugar, and MSG that cooks add to these dishes.

Moreover, visitors to Thailand may have romanticized ideas of where their food comes from: of farms and homesteads in Thailand, of mangoes and bananas pulled off of a neighbors tree perfectly ripe, of fresh ingredients found in markets that make their way to a kitchen within a day of their picking.

However, the reality is that these fantasies are more often than not oversimplifications of the Thai food industry. Indeed, those searching for organic produce may be quite shocked at the reality behind the fruits and vegetables found in Thailand’s markets and supermarket chains.

While its true that the large majority of fruit and veg is domestically produced and through some channels quite fresh, when investigating the chemical residue lurking on the outside and inside of the produce, we are sent down a rabbit hole that seemingly never ends.

In this post, I explore that rabbit hole.

Pesticide Use: Law, Evaluation, Control, Contamination

A major exporter of rice, rubber, corn, tropical fruit, and cassava, Thailand’s farmlands supply many of the world’s countries with bulk produce — so much so that it equates to about $10 billion USD per year.

To meet this demand, the Kingdom relies heavily on pesticides to control insect populations and increase the yield of said crops. In the past, the country has lost nearly 50% of its produce to insect scourges and other threats, so needs must, right?

Over the past ten years, Thailand’s agricultural exports have risen to make up at least 40% of the country’s GDP; therefore the nation’s use of pesticides has exploded exponentially to nearly four times the initial amount.

While this increased use may benefit crop yields, it also threatens the health and safety of this produce and makes it difficult for the government to regulate pesticide use in rural Thai farms.

Chemicals to combat insect infestations and other bacterial threats to crops include herbicides, insecticides, fungicides, plant growth regulators, and other pesticides.

Thailand is fourth out of 15 Asian countries regarding the severity of pesticide reliance, and over-spraying plants has contributed to issues like insect resistance and pest resurgence.

In an attempt to mediate the effects of these hazardous chemicals, the Royal Thai Government has enacted Hazardous Substance Act B.E. 2535 (HSA), which seeks to control the use of these harmful chemicals and reduce the risks of handling pesticides.

Corrosive and explosive chemicals are regulated by the act, as are toxic chemicals, pathogenic substances, radioactive material, and pesticides: in total there are 1,233 substances regulated.

The HSA is used to regulate most hazardous substances used in Thailand. It also seeks to prevent harmful exposure of these chemicals to people and the environment.

As enforcement, the Royal Thai Government created the Hazardous Substance Committee (HSC) to regulate chemical use across the Kingdom. Unfortunately, the targeting of specific (and harmful) chemical groups has negated the efficacy of this regulatory group. In addition, issues arise when pesticide samples are taken and are measured at differing ‘acceptable levels.’

Alarmed that your food contains pesticides at all? Most produce does, even in trace amounts. Many governmental agencies have established a standard called the Maximum Residue Level (MRL), which is the acceptable amount of chemical a food can contain (measured in milligrams of chemical per kilogram of produce) — this is not a safety measure.

In Thailand, it’s not uncommon for MRL values to have conflicting regulation standards, causing mass confusion in the food industry, and allowing for potential mistakes when it comes to the amount of pesticides (and antibiotics, bacteria, mold, micro-organisms, borax, formalin, and toxic coloring) included in foods.

Because of these flawed regulatory measures, an increased amount of pesticides are present in produce, causing import countries to complain about the potential safety of the food (and initiate trade issues).

Levels of Pesticides in Thai Produce

While visitors to the Kingdom may believe that their food is farm-fresh, the implications could be overwhelmingly negative, based on the farmer and their pesticide practices. While MRL regulation is still faltering in some regulatory agencies, those who regularly consume Thai produce are putting themselves at risk.

A non-profit agency, the Thailand Pesticide Alert Network, has reported that nearly 64% of Thai produce exceeds its MRL, and should be deemed unsafe.

On a larger scale, studies found that produce from some provinces in Thailand contained a much higher rate of pesticide residue than their counterparts from developed countries.

After studying Chinese kale, pakchoi, and morning glory, scientists detected pesticides 97-100% of the time, regardless of whether the vegetables were purchased in a local market or in a supermarket.

In addition, researchers found that the pesticide levels in the vegetables exceeded their respective MRL at 35-48% for Chinese kale; 55-71% for pakchoi, and 42-49% for morning glory.

Interestingly, the lower percentage of the range was attributed to supermarket produce; the higher percentage was attributed to local market produce.

On average, there were 28 pesticides used, including aldrin, atrazine, captan, carbaryl, carbofuran, carbosulfan, chlormefos, chlorpyrifos, chlorothanlonil, cypermethrin, deltanethrin, diazinon, dichlorvos, dicofol, chlorpyrifos… the list goes on.

These chemicals can cause a host of issues in those who accidentally come in contact with undiluted concentrations or trace residues, including neurological effects, nervous system malfunctions, kidney damage, headaches, dizziness, vomiting, muscle spasms, a reduced ability to fight infection, birth defects, and damaged reproductive organs.

While these findings are significant, please note that researchers chose produce from certain markets and provinces in Thailand, including Bangkok, Nakhon Pathom, Nonthaburi, Ayutthaya, Pathumthani, Samutsakorn, and Nakhon Ratchasima.

Researchers noted that it was difficult to obtain information about the suppliers and their pesticide practices. The study also clarified that the findings were exclusive to three target vegetables and a number of providers in central Thailand. Sample sizes were small, and the study was targeted.

In short, this study cannot be presumed representative of practices all over Thailand.

Farmers Poisoned by Pesticide Use

The sad reality of farming is that many in the industry are poisoned by exposure to these chemical pesticides.

While reported numbers rise into the thousands, scientists from the Ministry of Public Health are hesitant to confirm the veracity of these numbers, as they note that many farmers who fall ill from pesticide use may not report their problems to a local doctor or emergency care center.

While reports from the ‘90s suggest a range of 4,000-5,000 affected, studies indicate that the real number of farmers affected could total nearly 40,000 annually (Ref: ipm-info.org)

One should note at this point that some farmers increase their own risk of being poisoned by not following government guidelines: not using proper protective clothing, over-using pesticides and by using banned pesticides.

The Department of Agriculture concluded in a study that nearly 68% of vegetable farmers in Kanchanaburi were affected by some type of pesticide poisoning. Another study indicates that 90% of Thai farmers are impacted by agricultural chemicals.

A local farmer, Mr. Manit Boonkiaw who grows vegetables in Nonthaburi Province attested to the use of chemicals, saying:

Spraying was carried out all the year. One day I would spray and the next day the crop would be harvested and sent to market. I knew how dangerous that was. I always had headaches and felt dizzy after spraying pesticides, so I never used to eat those vegetables. I used to have a small plot that I didn’t spray; those were the vegetables for our own consumption.

The sobering reality for farmers across the Kingdom is driven by the demand for cheap food and large yields of it. Mr. Boonkiaw continues:

I know a lot of vegetable farmers who would like to reduce the amount of pesticides. They know that pesticides cost a lot of money and are bad for their health, but they are worried about the market situation. The middlemen don’t care about pesticides; they never ask what chemicals have been used. And the consumers want cheap vegetables that look good. They should realize that the good-looking vegetables are often contaminated with dangerous pesticides. If consumers would pay a better price for non-chemical vegetables, a lot more farmers would grow them. (Ref: ipm-info.org)

Organic Vs Safe Food Labelling

While the realisation that pesticide laden foods are affecting both consumers and farmers may lead some to pay closer attention to their produce, it’s not always so easy.

The increase in demand for ‘safe’ foods has resulted in a number of marketing techniques wherein fruits and vegetables are labeled ‘pesticide safe.’

The intention isn’t necessarily to mislead, but studies show people often mistake these foods for ‘organic’ or ‘pesticide free’.

The authorities have set standards for ‘safe’ food that are not as stringent or as regulatory as those deemed ‘organic’, and it doesn’t mean pesticides aren’t present.

‘Safe’ food is tested to make sure that residues are within the MRL, whereas organic produce does not use pesticides at all.

In Thailand, organic food is certified through the Organic Agriculture Certification of Thailand (ACT). Much of the country’s organic goods are produced by Green Net Cooperatives — both initiatives are covered by the Earth Net Foundation, which has a vested role in bringing organic farming to the hills of Thailand.

Their mission is moral, but the progress is slow. Only one out of 5,000 rai of farmland is currently organic.

And while the push for organic is noble, it isn’t always 100% effective. As has been seen in countries in the western world, organic crops are often infected by spraying in adjacent fields. And of course, some growers may not be entirely honest.

In 2016, the Bangkok Post reported that nearly 25% of organic-certified produce had been found to contain some type of pesticide residue. These foods included red chilli, basil, long beans, Chinese kale, Chinese cabbage, morning glory, tomatoes, cucumbers, oranges, guava, dragon fruit, papayas, and mangoes.

Though the organic movement has had some difficulty spurring momentum, the idea of growing food without pesticides is undeniably more healthful and environmentally friendly than the current standard agricultural processes. But the issue lies in educating consumers about the differences between organic, safe, and chemical-free certification standards in order to help the population make healthier choices based on scientific standards and regulatory limits.

Effects of Pesticides on Public Health

Perhaps the most devastating results of pesticide use are the health repercussions for those in close contact with food production or those who routinely consume tainted produce. Among these are the unborn.

Studies have shown that nearly 200,000 children born in Thailand annually to agricultural workers are at risk of exposure to toxic pesticides while still in the womb. Those that do not grow up on a farm are at risk for toxicity through diet, home, and other environmental factors.

Researchers found that women who worked in agricultural occupations were much less likely to consider the use of pesticides as unsafe for either themselves or their developing child. Risk was not mediated because of pregnancy.

In other studies, researchers have looked for health symptoms associated with pesticides from rice farming. These scientists studied blood samples to draw conclusions, and found that rice farmers had an increased difficulty in breathing and experienced chest pain, dry throat, cramps, numbness, diarrhea, and anxiety. The scientists concluded that exposure to pesticides in the rice fields may be associated with illnesses of the respiratory tract, in addition to muscle issues.

Children in farming communities are also not immune to the effects of these harmful chemicals.

Researchers studied children who reside in agricultural areas like Pathum Thani Province, and found that these communities of 6-8 year olds had higher urine levels of organophosphate pesticides than did children who lived in residential areas. An increased presence of this pesticide has serious implications for the future development and health of the child.

Markets vs. Supermarkets

While Westerners generally associate market produce as the ‘healthier,’ and the more ‘natural,’ those living in Thailand would do well to adjust those notions after reading a couple of the aforementioned studies.

It’s easy to consider local, independent sellers to have produce that seems more “organic” because the crops appear to be local and hearty. Often the produce looks very organic because it’ll show obvious signs of pest invasion — for instance, chewed leaves, and even an odd caterpillar.

But, as previously explored in the study regarding Chinese broccoli, the pakchoi, and the morning glory, local markets proved to have higher MRL of pesticides than did supermarket produce.

Pesticide Risk by Province

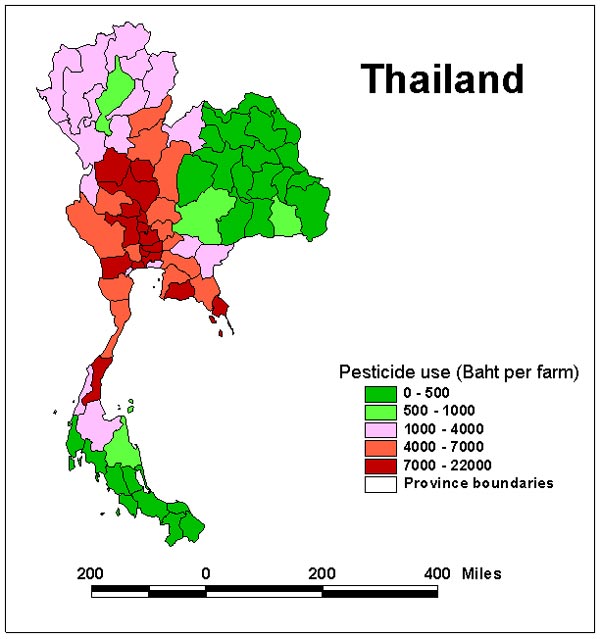

While certain studies of Thai produce highlight specific provinces or regions of the Kingdom as producing unsafe or potentially harmful produce, it can be helpful to take a step back and view the country as a whole.

In a study that measured the amount of money dedicated to pesticides on each farm annually, scientists were able to map out patterns of pesticide use over the entire country.

Northeastern Provinces averaged 388 Baht of pesticides per farm, annually, while the southernmost tip of the Kingdom averaged 1021 Baht/farm — making it statistically likely that food from these regions is the least contaminated.

Provinces in Central Thailand, averaging 7,094 Baht/farm likely have the most pesticide residue in food, while regions to the north — averaging 3622 Baht/farm — are in the moderate range of pesticide use.

Environmental Effects

And of course, no discussion of pesticides would be complete without an investigation of how these chemicals are affecting natural resources, like forests, animals and water.

Pesticides don’t just kill pesky creatures that eat crops; they soak into surrounding ground and kill useful insects that help support the circle of life by pollinating, producing honey/nectar and providing a protein source to other animals.

Harmful chemicals can leak into bodies of water like rivers, irrigation canals, rice paddies, and ponds and kill creatures like fish, frogs, turtles and snakes. As smaller animals are contaminated, larger predators are poisoned after hunting them.

In this way, chemicals are carried up throughout the food chain. The effect of pesticides on animals in Thailand is tangible — the endangered species list contains over 40 species of mammals and over 100 different types of birds.

Organochlorine pesticides – mentioned in the section about children living in farming communities – continue to be an issue as they perpetually contaminate large bodies of water.

There are major levels of these compounds in rivers of Southern Thailand. Effects include endocrine disrupting diseases, like breast, testicular and prostate cancer. Bangkok’s Chao Phraya River has been found to have high levels of these pesticides.

You can read more on this study here.

Summary & Advice

While it may be counter-intuitive, studies show that shopping for produce at supermarkets over local market stands may help consumers avoid dangerous MRL levels and pesticide contamination.

While the wide use of pesticides has caused concern, there are foods you can buy in Thailand that are generally free from pesticide levels.

For example: Researchers found that pesticide residue in watermelons and durians were significantly lower than these fruits’ recommended MRL level. Previous studies showed that Chinese cabbage was also free of pesticide contaminants.

Health conscious consumers can also avoid toxic pesticides by avoiding off season produce. The head of the Biodiversity Sustainable Agriculture Food Sovereignty Action Thailand group (BioThai) — Kingkorn Narindharakul Na Ayudhaya — noted that those concerned can “mitigate the risk by avoiding off-season and popular legumes.”

Those flocking to supermarkets in hope of finding safe food have a friend in Samrit Intaram, the Manager for The Mall Group (a shopping complex business). Mr. Intaram noted that his company decided to create a market for non-chemical products, using independent testing to determine chemical levels.

After deciding that his stores should only have pesticide-free vegetables, he vowed to buy exclusively from certified organic growers. These growers include farms like Lemon Farm Pattana Cooperatives, who sell food in eight stores around Bangkok.

While organic farming and a safe food practices may just be gaining a foothold in fertile Thailand, be assured, a revolution in food is coming.

no

no NO

NO no

no